Seven Layer Chocolate Cake

This essay was part of a series of “lasting Yankee Stadium†memories published prior to the last game at the Stadium.

Bronx Banter | September 22, 2008

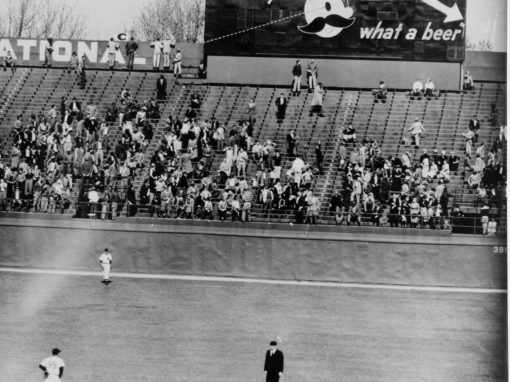

May 18, 1962 was a raw spring night in the Bronx. A mean chill filled Yankee Stadium suppressing attendance at the Friday night game between the Yanks and the Minnesota Twins. A forgotten tributary of the Harlem River, on whose banks the stadium was built, runs on a diagonal from left field toward the hole between third and short—like a cut off throw. The ancient waterway, Cromwell’s Creek, buried deep beneath the sedimentary rock of urbanization, asserted itself in the dew and chill of that otherwise fine Friday evening. Mist enveloped the scalloped copper frieze that ringed the upper deck of the Stadium. I remember thinking: if Mick hits one tonight nobody will ever see it again.

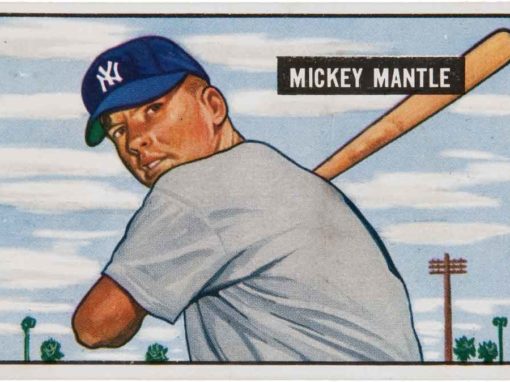

That was the thing about Mantle: you never knew what might happen when he stepped to the plate or what might happen to him.

My father, who grew up on the other side of the Harlem River cheering for the Giants from a rocky perch on Coogan’s Bluff, had gotten box seats behind the dugout along the third base line. It was the best seat I would ever have in a ballpark until I went to work as a sportswriter fifteen years later.

I was ten years old that sweet evening. What could be better-a visit to see The Mick and a sleepover at my grandmother’s? Her apartment was just up the street in a building called The Yankee Arms, a long, loud foul ball from home plate.

Mickey was my guy but I was grandma’s girl, her favorite, I thought (as did all her grandchildren). I knew this because although she loved frilly things and rose sachet, because canasta, not baseball, was her game, because in the 20 years she lived in the shadow of the ballpark she was never once tempted to step inside, despite all this she put on her mink stole and open-toed shoes and took me to Saks Fifth Avenue to buy my first baseball glove. It was an odd place to go in search of a mitt but she only wanted the best for me.

Providence intervened—a mannequin in the front window had a Sammy Esposito glove on her hand. “We’ll have that one,†my grandmother told the flummoxed salesman, who pointed out it was not for sale. He was no match for a Jewish grandmother, mine anyway. I took Sammy home; I took Sammy everywhere, including the stadium on May 18, 1962.

My grandfather, a manic-depressive immigrant tailor, had made me two identical wool, plaid skirts, one in tones of beige, brown and gold, the other in red and green, Christmas-tree green, perfect for Hanukah. They were reversible and indestructible. A whole wardrobe, these skirts. They went with everything and nothing. He was in a manic mode when he sewed them; their oscillating hems reflected his ups and downs.

In an act of filial devotion (and parental betrayal), my mother had made it a condition of attendance that I wear one of these atrocities. I chose the more muted tones and an overly generous straw-colored Irish cable knit sweater over a white turtleneck. I looked like a pre-pubescent haystack.

In an act of solidarity for which I remain grateful five years after his death, my father went to the concession stand and bought me an adult-size Yankee cap, large enough to hide most of my embarrassment.

I knew it was going to be Mick’s year. It had to be after the disappointment of 1961. God owed him after allowing Roger Maris to claim Babe Ruth’s title as home run king. Being second fiddle made him more loveable to the masses, but not to me–I couldn’t love him anymore than I did already.

“In 1961 I became an American hero because he beat me,†he would say later. “He was an ass and I was a nice guy. He beat Babe Ruth and he beat me so they hated him. Everywhere we’d go I got a standing ovation. All I had to do was walk out of the dugout.â€

In his first three at-bats that night, Mick walked and scored twice. With Roger Maris and Yogi Berra out of the lineup, he was the Yankee offense. When in the top of the seventh, Whitey Ford gave up a two-run home run to Harmon Killebrew, my mother said she had seen enough. I ignored her. An inning later with the Yankees trailing 4–3, she gathered her belongings.

With the Yanks down by a run and Mick due up fourth?

She pursed her lips and sat down. The murmuring began in the bottom of the ninth when Yogi was sent up to pinch-hit—Mickey was at the bat rack. Berra popped out to short. But then Tommy Tresh singled, a measly infield hit to be sure but enough to get Mick into the on-deck circle. There he was swinging a bat with that graceful torque of possibility. The big blue seven was almost jumping off his back. The roar could be heard up the street in my grandmother’s parlor where, she feared, the reconstructed leg of the grand piano in the parlor would succumb to partisan vibrations.

Joe Pepitone stepped to the plate. He was my mother’s favorite, though only because she liked the feel of his name on her tongue—â€Pepe! Pepe!â€â€”the worst reason ever to like a baseball player. A deep fly ball to center, still death valley then, moved Tresh into scoring position and brought Mantle to the plate.

knew it was going to be Mick’s year. It had to be after the disappointment of 1961. God owed him after allowing Roger Maris to claim Babe Ruth’s title as home run king. Being second fiddle made him more loveable to the masses, but not to me–I couldn’t love him anymore than I did already.

I told you.

Minnesota manager Sam Mele brought in Dick Stigman to face him and ordered him to throw only low curve balls. The first one was too high. Batting right-handed, Mickey hit a vicious grounder to deep to short. Out of the corner of his eye, he saw Zoilo Versalles, the Minnesota shortstop, fumble the ball and summoned a burst of remembered speed. He collapsed five steps from the bag, having torn the adductor muscle away from the bone. He looked like a dancer in mid-leap, his legs extended beyond reach or reason. He hung there for an instant, or so it seemed, before the force of gravity sucked him to the ground, splayed in the base path. “It was like a deer getting shot at mid-stride,†the New York Post reported the next morning.

He was road kill.

The time on the big Longines clock in right center field said: 10:23 p.m. Everyone in the ballpark stood, all 20,112 of us, including my mother, the one thing he couldn’t do. He later said he never heard a big place get so quiet so fast. He refused the stretcher proffered by the loyal trainer and was carried from the field on his teammates’ shoulders. He showered on crutches while up the street I tried to enjoy my grandmother’s seven-layer chocolate cake.

That meaningless, fateful bouncer to short was emblematic of Mantle—going all out all the time, whether swinging for the fences or hustling down the line. He played so hard he tore himself apart.

As always with Mantle, the injury was worse than originally feared. He had injured his left knee, the good one, when he fell. He would never be the same.

The Yankees lost 14 of the 28 games he missed. After they beat Willie Mays and the San Francisco Giants in the World Series, he was named the year’s Most Valuable Player, the third and last time he won the award. He said Bobby Richardson deserved it more.

My father took me back to the Stadium six years later to say goodbye to The Mick. It was 1968. God was dead; Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King had been murdered; my grandmother had been buried in a family plot in Queens, hard by the Long Island Expressway; and Mickey was getting ready to retire.

I don’t remember the date, the opponent, the score. The Senators, perhaps? A Sunday double-header, maybe? I remember that my father drove me past my grandmother’s front window, that he purchased the best seats available, which weren’t very good, behind an old steel pillar just to the left of home plate, field level but tucked back beneath the deck above.

I remember how my feet stuck to the unguent concrete suffused with decades of soda pop and cotton candy. I remember how the temperature rose—seemed like 20 degrees—when we stepped into the sun.

I don’t remember anything that Mickey might or might not have done that day. A methodical search of newspaper clipping files and Retrosheet’s database has yielded no clues. Memory refuses to give up its secrets. It doesn’t matter. He was there and so was I.

On Thursday night, I took the train uptown to say goodbye to Yankee Stadium. I walked up 161st Street past the drugstore where my grandmother got her Insulin prescriptions filled, past the store front that used to house the G & R Bakery where a Torah once resided behind a glass window above the bakery rack. I rode the elevator to the second floor of the Concourse Plaza Hotel where Mickey and Merlyn lived as newlyweds and where I once attended High Holiday services with my grandmother and my Sammy Esposito glove. (The ballroom where she prayed for my future is long gone). I stood beneath her window at the corner of 157th and Walton Avenue and decided not to knock on the door of her old apartment. I rode the escalator to the upper deck from which I could see her building and took my seat for the last time at the Stadium.

I expected to be overwhelmed. I expected to feel old, sad, something. What I felt was restless and annoyed at how early the popcorn sold out—and oddly disconnected from the infrastructure of my childhood. Later, I read somewhere that Bobby Richardson, the great Yankee second baseman, had experienced much the same thing. After all, he pointed out, this Yankee Stadium was not where he had played. It was not where Mickey fell in 1951 and not where he fell again one raw Friday night in May 1962. Not where I made up my mind that he wouldn’t object if I had a piece of my grandmother’s seven-layer-cake despite his legacy of pain.

More Essays