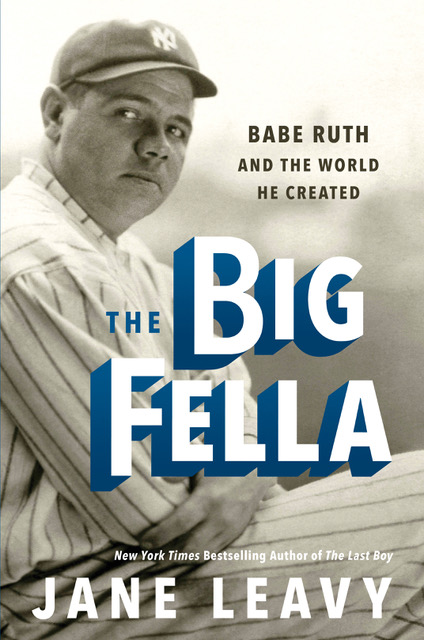

THEBIG FELLA

From Jane Leavy, the award-winning, New York Times bestselling author of The Last Boy and Sandy Koufax, comes the definitive biography of Babe Ruth—the man Roger Angell dubbed “the model for modern celebrity.”

He lived in the present tense—in the camera’s lens. There was no frame he couldn’t or wouldn’t fill. He swung the heaviest bat, earned the most money, and incurred the biggest fines. Like all the new-fangled gadgets then flooding the marketplace—radios, automatic clothes washers, Brownie cameras, microphones and loudspeakers—Babe Ruth “made impossible events happen.” Aided by his crucial partnership with Christy Walsh—business manager, spin doctor, damage control wizard, and surrogate father, all stuffed into one tightly buttoned double-breasted suit—Ruth drafted the blueprint for modern athletic stardom.

His was a life of journeys and itineraries—from uncouth to couth, spartan to spendthrift, abandoned to abandon; from Baltimore to Boston to New York, and back to Boston at the end of his career for a finale with the only team that would have him. There were road trips and hunting trips; grand tours of foreign capitals and post-season promotional tours, not to mention those 714 trips around the bases.

After hitting his 60th home run in September 1927—a total that would not be exceeded until 1961, when Roger Maris did it with the aid of the extended modern season—he embarked on the mother of all barnstorming tours, a three-week victory lap across America, accompanied by Yankee teammate Lou Gehrig. Walsh called the tour a “Symphony of Swat.” The Omaha World Heraldcalled it “the biggest show since Ringling Brothers, Barnum and Bailey, and seven other associated circuses offered their entire performance under one tent.” In The Big Fella, acclaimed biographer Jane Leavy recreates that 21-day circus and in so doing captures the romp and the pathos that defined Ruth’s life and times.

SABR Seymour Medal Winner

Best book of baseball history or biography published in 2019Â

The same insight and verve that attracted readers to Leavy’s portraits of Mickey Mantle and Sandy Koufax manifest themselves here as she traces the improbable transformation of the insecure little George into the imposing Sultan of Swat, master of the diamond and unparalleled national celebrity…. An American icon brought to life.

– Booklist (starred)

Jane Leavy could write the biography of a tube of toothpaste and I’d be first in line to buy it. Jane Leavy on Babe Ruth? Home run! Think you know the Babe? Not a chance—not until you read The Big Fella.

– Jonathan Eig

Entertaining and colorful…. Leavy’s captivating biography reveals Ruth as a man who swung his bat with the same purposeful abandon that he lived his life.

– Publishers Weekly, starred

Does the world need another biography of Babe Ruth? If it’s this one, then the answer is an emphatic yes … Sparkling, exemplary sports biography, shedding new light on a storied figure in baseball history.

– Kirkus, starred

Meticulously researched over eight years and richly detailed, it’s as close as we’ll ever come to meeting the legend and watching him in action.

The Big Fella is a must-read for Babe Ruth fans, baseball history buffs, and collectors. Above all, it is a major work of American history by an author with a flair for mesmerizing story-telling.

– Forbes

Magnificent…. All this is only to touch on the wealth of research, detail and astuteness of observation that make up The Big Fella. Some of it is sad…. But the winning side of the Babe’s life predominates in these pages and in history.

– Wall Street Journal

Jane Leavy writing a book about Babe Ruth is the biggest thing that has happened in my life since Santa Claus visited my classroom in the second grade. This is Babe Ruth off the diamond and out of uniform, a very flawed human being but still very much a hero, a man who could lift an army of beggars and wannabes onto his back and carry them to their dreams.

– Bill James

Leavy has cleared the bases with a compelling account of the game’s greatest, Babe Ruth. Leavy brilliantly describes the complexities that accompany an elite talent and the blessing and curse of stardom while documenting the essential role of an attorney to provide vision, create a protective umbrella, and facilitate the most important goal for a unique athlete: self-understanding.

– Scott boras

Covers all aspects of Ruth’s massive life, bringing true empathy and impressive depth of knowledge to her complex subject.

– Boston Globe

…paints a sensitive and humorous portrait of a flamboyant figure who exploited technological transformations, public appetites and his athletic prowess to forge a new sporting celebrity.

– Washington Post

The result is the most complete account yet of Ruth’s complicated, tragic family life, including siblings who died young, parents who separated and, most famously, being shipped off to St. Mary’s Industrial School for Boys in Baltimore.

– Newsday

[Leavy} manages to write one of the best documentaries of America’s first decades of world domination. At well over 600 pages, The Big Fella, beyond being the premiere biography about the King of Crash, is a book for all history buffs, not just fans of the New York Yankees, baseball, or sports in general.

– Philadelphia Inquirer

What sets “The Big Fella: Babe Ruth and the World He Createdâ€Â apart from earlier attempts to identify the true essence of the man is an unprecedented look back into Ruth’s long-neglected childhood and a magnified focus on how his tremendous popularity helped birth the cult of personality in America.

– The Baltimore Sun

Is it even possible to have enough great Babe Ruth books in the world? No! This Jane Leavy opus on the Babe, “The Big Fella,” is just amazing. Filled with fabulous tales. Tell me you wouldn’t have wanted to follow the Bambino around on a barnstorming tour in 1927. Now you can!

– Jayson Stark

Captures Ruth’s outsize influence on American sport and culture…. Leavy’s conceit allows her to stake out some untrod turf. But she also makes a compelling case that to appreciate the adulation Ruth soaked up in October 1927 is to understand his contribution to American life in full.

– New York Times Book Review

There have been numerous books written about the enormous life of Babe Ruth…. Jane Leavy, though, manages to mine new material in her wonderful book…. Ultimately, Leavy provides a different perspective of a man who consistently broke the mold in sports and society.

– Chicago Tribune

Fascinating…reveals Ruth’s pioneering role in modern celebrity.

– The Guardian

Leavy always entertains, injecting necessary context about a sport that was just beginning to become a major advertising and marketing vehicle. She also evokes sympathy for the Babe … without excusing his sins and excesses. Leavy brings the larger-than-life slugger down to the size of a real human being.

– New York Magazine

Leavy’s study … is not just about baseball, but also a psychological portrait: what shaped The Babe and what made him tick in a world that couldn’t get enough of him (he thrived on it) and sucked him dry. It is an exhaustive visit inside the head of Mr. Ruth and a snapshot of his life brilliantly described.

– Winnipeg free press

Throughout the book, Leavy, through dogged reporting and astute analysis, strips away many of the myths and misconceptions surrounding Ruth’s life.

– Christian Science Monitor

Early in her seminal Babe Ruth biography, “The Big Fella,â€Â Jane Leavy, the gifted storyteller of bygone ballplayers, perfectly encapsulates his place at the intersection of America’s game, Americana and America today.Â

– Jeff Passan, Yahoo Sports

While The Big Fella is a lush and engaging biography of one of the most enigmatic and iconic characters of the 20th century, author Jane Leavy knocks this one out of the park by also giving readers an aperture into a transformative time in American history … Leavy proves to be a dogged researcher and mines previously untapped sources … Leavy proves Ruth was an enigma to himself, too, and it’s her sharp prose that really propels this biography…

– WASHINGTON INDEPENDENT REVIEW OF BOOKS

Leavy documents a personal life marked by tragedy … But Leavy doesn’t write about how these terrible moments shaped Ruth’s personality and life, because it’s simply unknown. Ruth never really told anyone, and the hagiographic sports reporting of his era never delved into it. ..Leavy responds by doing the next best thing: painstakingly re-creating the mythical, larger-than-life role Ruth played in American culture at the height of his fame.Â

– SCOTT DETROW, NPR

The Big Fella

An Excerpt

Babe Ruth swept into the great hall of Manhattan's Pennsylvania Station either with or without two ladies of the night prominently clinging to his arm. He had or had not spent the night before in their company. Did or did not pat them on the derriere and tip them effusively, calling out to a pal among the assembled scribes, photogs, hangers-on, autograph addicts and redcaps gathered to see him off: "Coupla beauts, eh?"

Christy Walsh thrust himself into the scrum. Among other things, it was his job to make sure the story remained an either/or—either it wouldn't find its way into print until long after they were all dead or it would be forgotten in a blitz of favorable mentions of the visits Walsh had arranged to hospitals and orphanages, where Babe would be photographed being his best self.

It was Oct. 11, 1927, three days after Ruth and the Yankees had finished off a World Series sweep of the Pirates. Eleven days after he had hit his 60th home run, crowing as he rounded the bases, "Sixty! Count 'em, 60. Let's see some other sonofabitch do that!" Most Americans still thought the Babe was a happily married man—witness those photos of Helen, his wife, and their daughter, Dorothy, in the stands at Yankee Stadium during Games 3 and 4 of the Series—even though Babe and Helen had been legally separated for two years. In the fight to preserve that image, Walsh could count on the discretion of the newspaper beat guys on the payroll of the Christy Walsh Syndicate—a nationwide network of paid mythologizers—who doubled as Ruth's ghosts, but not on their editors if they got wind of the story. Not anymore.

Walsh's immediate task was to extricate Ruth from the mob that attached to him like an appendage. They had a train to catch. There was a ball game, a mayor and a governor waiting for them in Trenton, N.J., the first stop on a valedictory barnstorming tour of America that Walsh had organized to showcase Ruth and his fellow Yankees slugger and celebrity foil Lou Gehrig. Penn Station occupied seven acres of Manhattan real estate, stretching two city blocks along Seventh Avenue. The largest indoor space in the city, it was Ruthian in proportion. It was also a landmark in the professional relationship between Ruth and Walsh: It was here, on Feb. 21, 1921, that he had secured Ruth's signature on their first contract.

Walsh couldn't have imagined when he signed the Big Fella to that one-year deal that Ruth would get this big. That the money would get this big. That the job would get this big. In 1927, with Walsh's help, Ruth would become the first ballplayer to be paid as much for what he did off the field as for what he did on it. And Walsh was the first of his kind: the player agent-marketing impresario who made it all happen. What began six years earlier as an agreement to syndicate ghostwritten stories under the Babe's byline had become an entirely new kind of business: the management, marketing and promotion of athletic heroism. Together they were inventing a new way for athletes to be famous.

Walsh now controlled every aspect of Ruth's financial life: investments, annuities, insurance policies, endorsements, personal appearances and taxes. And he was involved in every aspect of Ruth's personal life too. He would say later, "I did everything but sleep with him." And one night, when only a single unoccupied berth was available on their overbooked Pullman, he even tried that. Ruth kicked him out of bed.

. . . . .

They were an unlikely pair. Born in St. Louis in 1891, Walsh was only four years Ruth's senior but now found himself acting in loco parentis, legally and otherwise. He was 29 years old, broke and out of a job when they met in 1921, having failed to succeed as a newspaper cartoonist, p.r. and advertising man.

Mantle was all but invisible until the coaches said, "Take your marks . . ." Hank Workman, a prospective first baseman, recalled, "They were timing guys from home to first. Nobody noticed Mantle up to that. He was very quiet and extremely shy. He would pull his cap down so far over his brow that you could hardly see his face. Then he ran. And I swear he was going so fast you could still see the tufts of dust in the air from his footprints a couple of feet back from where he was."

Walsh looked like he was born responsible. His birthday suit was probably three-piece. His slicked-back black hair might have been parted with a nun's ruler. A devout Catholic and son of Ireland, he pined for the old sod though he had never set foot on it. Ruth was all id; Walsh was all superego. Yes, it could be frustrating "handling these children dressed as adults," he would confide to his son years later. "But as long as they need you, you're safe. You make them believe they can't go on without you."

Walsh told so many versions of how they met that it was hard to keep track of them all. There was the version he told his brother Matt: how he found out the floor and room number of the hotel where Ruth was staying, climbed the fire escape, clambered through the window (magically open a crack), found Ruth in bed with a blonde, slapped the Babe on the butt, and said, "I want to represent you."

There was the one he told in Adios to Ghosts, his 1937 memoir, in which he staked out Ruth's apartment at the Ansonia Hotel on the West Side of Manhattan. Walsh was at the local deli where the Babe bought his beer, when the counterman got a telephone call. "Baby Root vants a case of beer. Right avay, right avay, and mine boy is gone. Yoi. Yoi. Yoi."

Ten minutes later Walsh was unloading beer in the Babe's kitchen and inquiring how much Ruth was paid for the ghostwritten accounts of each of his 54 home runs in 1920 published by the United News Service.

"Five bucks," said the Babe.

That came to $270 for the season—which was about all they were worth. Walsh said, "I can get you $500." Now he had the Babe's attention.

Walsh announced the creation of the Christy Walsh Syndicate in the March 19, 1921, edition of Editor & Publisher. Two weeks later, he placed a full-page ad in the same publication, touting the "greatest array of talent and genius ever offered American newspapers." That great array of talent he claimed to represent included filmmaker D.W. Griffith, whose secretary never actually let Walsh through the front door; Gene Buck, who was too busy running the Ziegfeld Follies to write the proposed Broadway column, "A Buck a Day"; opera diva Mary Garden, who boarded a ship for Europe without crafting a single word; and Jack Dempsey's fight manager, Jack (Doc) Kearns, who had the virtue of being available, which the Manassa Mauler was not. And of course, Babe Ruth, who had agreed to "write" two articles a week.

Walsh didn't invent ghostwriting. It was known as "the player-author evil" when Ban Johnson, president of the American League, threatened to ban Eddie Collins and Frank (Home Run) Baker from the 1913 World Series because of contracts they had signed with John Wheeler's Bell Syndicate. But Walsh perfected it as a business model. His initial plan was to syndicate ghostwritten copy for entertainers, giving a public voice to the still silent stars of Hollywood movies. But he quickly sized up the competition in the syndication racket and concluded it might be wiser to specialize in something they didn't offer: columns from clients who made daily headlines instead of one movie a year.

Walsh was selling a kind of fool's gold, whose value peaked as the 1920s grew into the golden age of sports and celebrity: bright, shiny words with little mettle that generated lots of cold, hard cash for author, subject and the syndicate man, casting a gauzy glow over the putative authors while offering readers the illusion of being in the know. In an era before radio delivered pregame, postgame, and in-game interviews, Walsh's fables were as close as baseball fans could get to hearing voices of faraway stars. No one knew what they sounded like anyway. So what if reading them required a willing suspension of disbelief?

Once he had Ruth under contract, other big baseball names quickly followed: John McGraw, Walter Johnson, Ty Cobb, Miller Huggins, Rogers Hornsby, Gehrig. Then came the gridiron greats: Notre Dame coach Knute Rockne, Pop Warner and Ted and Howard Jones. Walsh was a visionary. He saw that a new kind of stardom was emerging, one grounded in personality and amplified by marketing and technology. Fame got bigger, louder, more personal.

That's why the story about ladies of the evening accompanying the Babe to Penn Station would have legs whether or not it was true—and Walsh wasn't about to let it draw even the slightest attention away from his barnstorming operation. This was the third postseason tour Walsh had organized for the Babe and by far the most ambitious—21 cities in less than three weeks. By now he had the formula down. At every stop, Ruth and Gehrig would visit hospitals and orphanages, attend luncheons and banquets—hosted most often by the Elks or the Knights of Columbus, organizations to which Ruth belonged—give speeches (written by Walsh), praise local dignitaries, sign autographs, conduct pregame hitting exhibitions and captain teams composed of local semi-pros, bush leaguers and a few big leaguers in games between the Bustin' Babes and Larrupin' Lous, for which Walsh demanded a guaranteed flat fee. Up front. In some towns, Walsh recruited newspapers that bought Ruth's columns to sponsor the games, generating this front-page headline in the Tacoma Ledger in 1924: 5000 KILLED IN BATTLE FOR SHANGHAI, LEDGER BRINGS BABE RUTH TO TACOMA.

Walsh was doing everything he could to modernize the tour, arranging for still and newsreel cameramen to show up at as many stops as possible, preferably with marching bands and a throng of clamoring boys. He booked radio interviews wherever he could. He sold Collier's magazine on an exclusive story of the tour. He also gave exclusives to "girl reporters," whom he could count on for feminine fawning and teary-eyed puffery to round out the Babe's rougher edges. In 1926 he got Lorena Hickok, one of the first women to cover a sports beat for a major newspaper and later the first to receive a byline in The New York Times, to coo over Ruth in the society column of the Minneapolis Tribune. "What you most notice, after you have become accustomed to his size, are his eyes. Instead of being cold and keen and sharp, they are warm and amber colored and heavy-lidded, as clear and as soft as the eyes of a child."

But men also swooned. In Trenton, in front of an official crowd of 3,500 plus another 3,000 or so schoolboys, Ruth would twice circle the bases with children clinging to his arms and wrapped around his legs. Then, after a third home run, an army of boys chased him into the dugout, where he fell, heaving and sweating, into the laps of sportswriters and Trenton mayor Frederick W. Donnelly. "My God, they scared me stiff," Ruth said, taking a minute to catch his breath. He wasn't afraid for himself, he explained quickly: "I was afraid I would trample one of them—these spiked shoes would cut a kid's shoes off."

Ruth's fame was at least as great—and as hysteria inducing—as that of any Hollywood star. He was the first athlete to be recognized as an entertainer who transcended and expanded the parameters of athletic fame. Columnist W. O. McGeehan compared him favorably with Charlie Chaplin in a June 1927 column in the New York Tribune, writing, "If there were any way of appraising the drawing power of the Babe I think that he would be shown to be the greatest moneymaker as an entertainer for all time."

This marked a profound shift in the perception of athletes as performers. And Walsh was there to argue—or quietly prompt Ruth himself to argue—that he should be paid not just for what he did at the ballpark but for whom he brought to the ballpark. He was creating a whole new fan base. People who didn't know or care where first base was needed to see and be seen with Babe Ruth. People like Vin Scully's mother, a redheaded Irish girl just off the boat whose new beau took her to Yankee Stadium to learn about America. "One of the first things he said was, 'You must see Babe Ruth,'" said her son, who would become a defining voice of the game. "She had no idea what baseball was about. But that's how important it was. One of the first things this American wanted to show an immigrant was Babe Ruth."

. . . . .

Visionary though he was, there were limits on what Walsh could do to translate this star power into bargaining power. He was barred by tradition and by the thoroughly unbalanced balance of power in the game from representing Ruth's interests at the bargaining table with his baseball employers. As a result, agent Scott Boras said, Ruth never got his financial due from baseball. This would not change until 1970 when Marvin Miller negotiated a revolutionary collective bargaining agreement for the Major League Baseball Players Association. Roger Maris wasn't even permitted to bring his brother along with him to negotiate his '62 contract with the Yankees after breaking Ruth's home run record the year before.

On March 2, 1927 Ruth signed a three-year contract for $70,000 per with the Yankees. Most headlines hailed the negotiation as a success: It was the largest deal in baseball history. But Walsh was less enthused—in fact, he was disconsolate. He instructed the Babe to demand $150,000 a year and accept no less than $100,000. Wrote Westbrook Pegler in a syndicated column appearing in The Washington Post, "Mr. Walsh's disgust over the news that his fellow had quickly succumbed to the suasion of Edward Generous Barrow and signed for $70,000 a year was so poignant that he has not even mentioned that matter to the Babe since then."

Ruth predicted to reporters that he would have his best season ever—and he did, breaking his own record with 60 home runs. And thanks to Walsh he more than doubled his 1927 Yankees salary. On March 8, The Wall Street Journal took an unprecedented look at what Walsh liked to call "by-product money"—non-baseball income: "He scores homers by allowing his name to be printed on boys' underwear, caps and shoes," the Journal reported. "He gathers in royalties from manufacturers of all kinds of soft drinks and holiday souvenirs. No figures are kept, or at least made public, of the Babe's total income."

In fact, Walsh kept meticulous accounts of the income he generated for Ruth, down to the penny, less his commission. The ledger he prepared at the end of their contractual relationship in May 1938 documented every dollar Ruth earned through his management. One figure stands out in neon sizzle from the rest. In '27, Ruth earned $73,247 in by-product money, $3,247 more than his Yankee salary. Ruth's take-home pay that year was the equivalent of $26 million in today's purchasing dollars.

The $13,000 he earned that year from endorsements doesn't sound like much except that it was then twice the average major league salary. By addressing the subject of Ruth's financial portfolio, the editors of the Journal were acknowledging a new phenomenon in the American marketplace. He was the prototype for the modern athletic pitchman: Joe DiMaggio for Mr. Coffee, O.J. for Avis, Peyton Manning for everything. Walsh had created a blueprint for a business that would become synonymous with the catchphrase from the 1996 movie Jerry Maguire: "Show me the money."

For years, Walsh had waged a highly unsuccessful campaign to get the profligate Bambino on solid financial footing and convince him to save for the future. (In March 1926, Ruth had asked Walsh for a $4,000 loan.) By February '27, he realized it was time to resort to trickery. He convinced Ruth that it would be great p.r. to stage a news conference in Los Angeles on his 32nd birthday to announce that he was penalizing himself a thousand dollars for each year of misbehavior and putting it in a new trust fund with the Bank of Manhattan in New York. On Feb. 7, Ruth looked into the cameras and said, "Christy, I guess you have me convinced about the importance of saving a few bucks. You can penalize me a thousand dollars for each year. That'll make $33,000 to start with."

Collier's magazine: "To make it look real, the Babe was photographed signing the $33,000 over into an untouchable trust fund. The Babe later demanded his money back but found that the principal was beyond his reach forever and that he could have nothing but the interest." Newspapers across the country trumpeted the news of a new era of fiscal responsibility. The deal Walsh struck with the Babe was this: All ancillary income would go into the trust while Ruth kept his Yankees salary to live on and play with.

By September 1927, according to a widely syndicated story published in, among other places, The Baltimore Sun, Babe Ruth was the second most valuable human being in the United States, carrying a reported $5 million in life insurance, second only to department-store magnate John Wanamaker. Yankees general manager Ed Barrow quickly dismissed the story as "the bunk," telling The New York Times Ruth's life was worth no more than those of Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, Will Rogers, Gloria Swanson or John Barrymore, who each carried $3 million.

In denying the inflated report, Barrow actually conceded the point that Ruth was now an entertainer, an economic engine for major league baseball, the American League, and every American League city he played in—not to mention the Yankees, his family, his agent, every barnstorming town he visited, every sporting goods store he patronized and every brand of cigar he smoked.

. . . . .

Walsh couldn't have foreseen that a century after the fact historians would be analyzing, hailing and occasionally bemoaning his precedent-setting partnership with Ruth. But what Walsh did understand was this: Stars were no longer marketed just for their specific skills, but for themselves.

"From the beginning fame has required publicity," Leo Braudy wrote in The Frenzy of Renown, the definitive study of fame in America. "In great part the history of fame is the history of the changing ways by which individuals have sought to bring themselves to the attention of others and, not incidentally, have thereby gained power over them."

For Alexander the Great, that meant stamping his visage on the coin of the realm, where only gods had gone before. In the '20s, technology was producing what the historian Warren Susman called "new ways of knowing" almost as quickly as Ruth hit home runs. Everywhere there were new genres of information—and Walsh made it his business to harness all of them in his bid to stamp Ruth's mug on the American consciousness: screaming headlines on the back pages of the nation's tabloids newly consecrated to sports, comic strips, three-dot gossip columns, feature films and newsreels.

Fox Movietone premiered its first biweekly talking newsreels in New York in October 1927 and around the rest of the country in December, with highlights of the Army-Yale football game and a New York City rodeo—a prototype of the sports-highlight packages that would dominate TV sports news. With them came changes in memory. Spectators began to seek verification in the projection and repetition of imagery rather than trust their own recall.

Walsh was quick to take advantage of endorsement opportunities on the ever-expanding airwaves that now brought baseball into America's homes. Ruth would make bad romantic comedies, yak on talk shows, create comic strips to hawk breakfast cereal and cut gramophone records for the 44% of American households with Victrolas. He flourished in the camera's lens, lighting up with the explosion of each magnesium flare. The camera magnified every ridge and invaded every pore, revealing the tobacco stains on his uneven teeth and the crooked bite behind the famous grin. Each blast of powder made his face seem even bigger than it was, which was plenty.

The images were static, setup shots; the paparazzi were still decades in the future. Each of the "exclusive" photographs that Walsh orchestrated—and released to clients of the Christy Walsh Syndicate and stamped "No charge to Babe Ruthpapers, not available to others"—was purposeful. Every magazine in America—TIME, Vanity Fair, Liberty, Popular Science, American Boy and even Hardware Age—found a reason to put him on the cover. There was no pose he wouldn't assume. No one he wouldn't pose with. He was pictured with athletes: Dempsey, Tilden, Zaharias and Ed (the Strangler) Lewis. Generals: Alphonse Jacques of Belgium (outside the Palace Theatre in New York), Marshal Foch of France ("I suppose you were in the war?") and John J. Pershing. Animals: chimp, greyhound, pigeon, turkey (dead and alive), tortoise and lobster (on National Lobster Day). Royalty: King Prajadhipok of Siam and Queen Marie of Romania (he told her he was a king, too). Presidents: Coolidge, Harding, Franklin Roosevelt, George H.W. Bush as Yale's first baseman and Hoover, albeit reluctantly. ("A matter of politics," he said.)

And Walsh made sure there were photographers at every orphanage and tubercular asylum they visited. Not that the Babeneeded encouragement to pay these calls. At the Glen Lake Sanatorium in Minnesota in 1926, a photographer for the Minnesota Daily Star took what may be the least known and most affecting photograph of those visits: the Babe, surrounded by a tribe of sick children clothed only in loin-cloths. Ruth betrayed no hint of discomfort with their appearance or condition.

Ruth knew how far he had come from the boy whose parents abandoned him to the custody of the Xaverian Brothers at St. Mary's Industrial School for Boys in Baltimore and how fast it had all happened. When he filled out his 1927 application for Who's Who in America, he refused to name his occupation. "If they don't know," he said, "let them have their best guess."

On those gala evenings when he got all dressed up in a tux with his white-silk scarf to greet his public at some banquet or other, his daughter Julia recalled, he would stop at the front door of his Riverside Drive apartment to allow for a moment's inspection, asking the women in his life: "Am I a handsome fella or not?"

In that question, in the patent need for approbation beneath the homely mug, people saw themselves, or somebody they knew. They couldn't get close enough to him. But, oh, how they tried.

Read an Excerpt

“I believe in memory, not memorabilia,†Leavy writes in her preface. But in The Last Boy, she discovers that what we remember of our heroes—and even what they remember of themselves—is only where the story begins.